How Peer Attitudes Shape Everyday Choices Through Social Influence

Feb, 20 2026

Feb, 20 2026

Ever bought something just because everyone else had it? Or changed your mind about a movie, a habit, or even a political view because your friends seemed to feel differently? You’re not alone. This isn’t about being weak or easily led-it’s about how human brains are wired to fit in. Social influence is the quiet force behind most of the choices we make, especially when we’re unsure what to do. And it’s not just about loud peer pressure. Often, it’s the subtle, invisible pull of the people around us-our classmates, coworkers, or even just the people we follow online-that nudges us toward certain behaviors, brands, or beliefs.

Why We Copy Others Without Realizing It

Human beings are social animals. For thousands of years, survival depended on being part of the group. If your tribe ate a certain plant, you ate it too. If they avoided a river, you did too. Today, the stakes are lower, but the instinct hasn’t changed. When we’re uncertain, we look to others for cues. That’s called social proof, and it’s one of the strongest drivers of decision-making. A classic study from 1955 by Solomon Asch showed this power in action. Volunteers were asked to compare the lengths of lines. Everyone else in the room-actually actors-gave the wrong answer. Nearly three out of four participants went along with the group at least once, even when the correct answer was obvious. The brain didn’t just fake agreement. Brain scans from later studies show that when people conform, their perception literally changes. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the area linked to how we value things, lights up differently when we adopt a peer’s opinion. It’s not pretending. It’s re-calibrating.It’s Not Just About Being Liked-It’s About Belonging

Most people think peer influence is about wanting approval. But research from the 2022 PMC study by Negriff et al. found two deeper needs at work: being liked (which explains 34.7% of conformity) and belonging to the group (29.8%). These aren’t the same. You can be liked and still feel like an outsider. But if you feel like you belong, you’ll change your behavior-even if it costs you personally. Take vaping among teens. A 2021 CDC program called ‘Friends for Life’ didn’t just warn kids about health risks. It trained popular students to model quitting behavior. Why? Because in dense peer networks, influence flows through those who are socially central-not the loudest, but the ones others naturally look to. In schools where vaping was already above 25%, this approach cut 30-day use by 18.7%. The key wasn’t fear. It was social identity. Teens didn’t want to be the outlier. They wanted to be part of the group that was changing.Who You Listen To Depends on Status

Not all peers are equal. You’re more likely to copy someone you see as higher status-someone popular, confident, or respected. A 2015 study by Choukas-Bradley found that when teens saw a high-status peer act prosocially (like helping someone), they were 37.8% more likely to follow suit than when the same behavior came from someone of equal status. But here’s the twist: influence peaks when the status gap is moderate. Too big, and it feels unattainable. Too small, and it doesn’t feel special. The sweet spot? A status difference of 0.4 to 0.6 standard deviations. In real terms, that’s the difference between someone who’s well-liked and someone who’s the absolute top. This isn’t just about teens. In workplaces, people copy the behavior of managers they admire, not just because of authority, but because they assume those people know something they don’t. That’s why companies that train ‘opinion leaders’-not just managers, but respected team members-see better adoption of new policies, healthier habits, or even recycling programs.The Hidden Trap: Misreading the Group

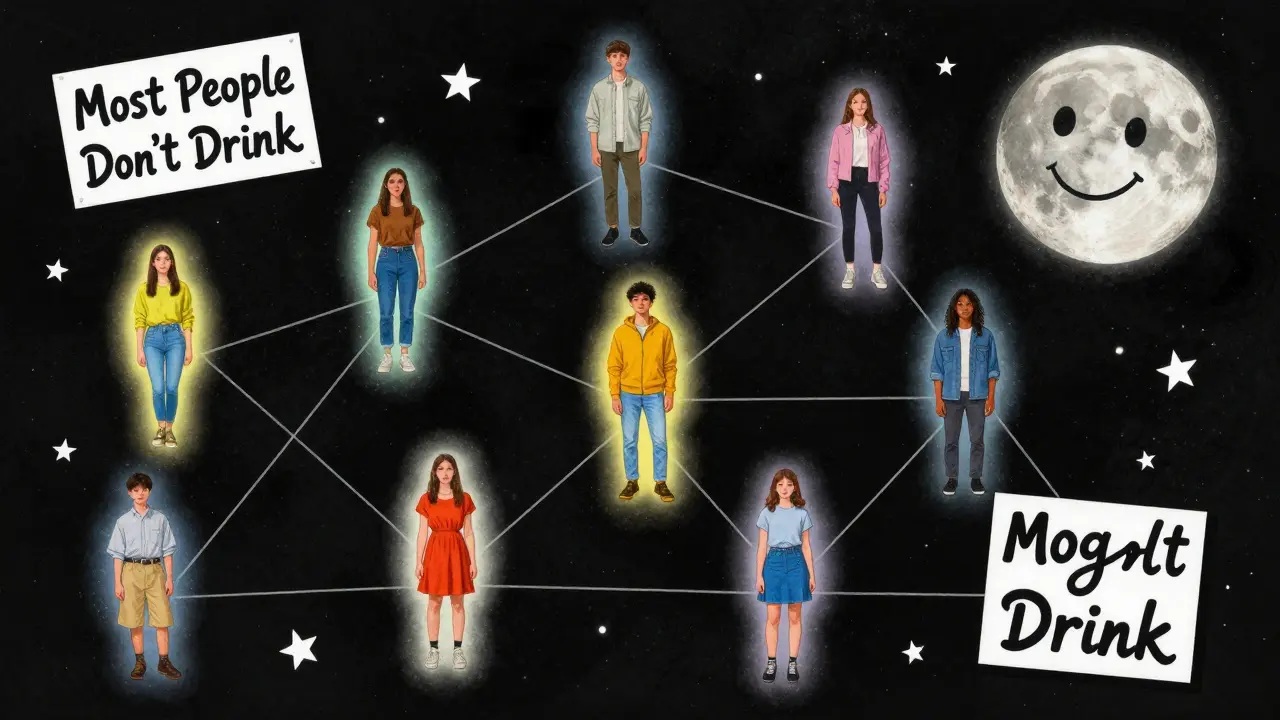

One of the biggest mistakes in social influence is assuming everyone thinks or acts the way you think they do. This is called pluralistic ignorance. A 2014 study by Helms et al. found that 67.3% of teens overestimated how much their peers drank, smoked, or used drugs. The gap wasn’t small-it was 20% or more. And here’s the kicker: the more you think everyone else is doing it, the more you feel pressured to join in. That’s why many anti-drug campaigns backfire. Telling teens, “Most people your age don’t use drugs,” actually works better than scaring them with statistics. It corrects the misperception. This also explains why social media is so powerful. When you see 500 likes on a post, your brain assumes it’s popular, even if the account has 10,000 followers and only 5% engage. Algorithms amplify this. They show you what’s trending, not what’s true. That’s why a trend like “clean eating” or “minimalist living” can explode-not because it’s better, but because it looks like everyone’s doing it.When Social Influence Helps-Not Hurts

We often think of peer influence as negative. Peer pressure = bad. But research from Mitchell Prinstein (2021) shows it’s a double-edged sword. In school settings, teens who conformed to peers who studied hard saw a 0.35 standard deviation increase in academic performance. That’s the equivalent of moving from the middle of the class to the top third. In contrast, conformity to peers who used substances increased drug use by 0.28 SD. The difference? The group norm. This is why interventions that work focus on changing the group’s default behavior, not just the individual. A program called ‘Be Real. Be Ready.’ boosted adolescent emergency preparedness by 29.4% by having peer leaders model practical actions-like packing a go-bag or learning CPR-and framing it as something smart, responsible people do. It wasn’t about fear. It was about identity. The kids didn’t want to be the one who wasn’t ready. They wanted to be the one who was.

Why Some People Are More Susceptible

Not everyone is equally influenced. Research shows susceptibility varies between 0.15 and 0.85 across populations. Some people are wired to be more sensitive to social cues. Adolescents, especially, are more vulnerable because their brains are still developing the ability to weigh long-term consequences. But it’s not just age. Personality, culture, and even network structure matter. In collectivist cultures like Japan, conformity rates are more than double those in individualistic cultures like the U.S. (23.4% vs. 8.7%). Why? Because in Japan, group harmony is a core value. In the U.S., independence is prized. But even within the U.S., social networks matter. A 2010 study of 1,245 Dutch teens found that those in dense peer groups (where everyone knows everyone) were more likely to adopt depressive symptoms from friends-not because they were sad, but because the group’s emotional tone became contagious.What This Means for You

If you’re trying to change your own behavior-whether it’s eating better, saving money, or quitting a bad habit-don’t just rely on willpower. Look at your social environment. Who are you spending time with? What are they doing? If you want to be more active, find friends who walk or bike. If you want to cut back on screen time, join a group that does too. Influence flows both ways. If you’re a parent, teacher, or manager, don’t try to control behavior by lecturing. Identify the quiet influencers in the group. Train them. Empower them. Let them model the change. It’s far more effective than any policy or poster. And if you’re designing a product, campaign, or app? Don’t just push features. Push identity. People don’t buy products. They buy the version of themselves they become when they use them. A toothbrush isn’t about enamel. It’s about being the kind of person who takes care of their health. A fitness app isn’t about calories. It’s about being the kind of person who shows up.What’s Next for Social Influence Research

AI is now being used to predict who’s most likely to be influenced. DeepMind’s 2023 model analyzed social media patterns and predicted susceptibility with 83.7% accuracy. That’s powerful. But also worrying. The Electronic Frontier Foundation found 147 platforms in 2023 selling “influence-as-a-service” to advertisers-tools that let companies target people based on how easily they’re swayed by peers. The National Academies warned in 2024 that we’re entering an era of hyper-personalized social manipulation. The same tools that help reduce teen vaping could be used to push junk food, misinformation, or unhealthy beauty standards. The challenge isn’t to stop influence. It’s to make sure it’s used ethically. Because social influence isn’t the problem. The problem is when it’s hidden, unregulated, and exploited.Is social influence the same as peer pressure?

No. Peer pressure is usually forceful, overt, and negative-like being bullied into doing something. Social influence is broader and often subtle. It includes everything from unconsciously copying a friend’s style to adopting a new habit because your coworkers do it. It’s not always intentional, and it’s not always bad. In fact, most of the time, it’s just how humans learn.

Can social influence be used for good?

Absolutely. The CDC’s ‘Friends for Life’ program reduced teen vaping by 18.7% by training popular students to model quitting behavior. Schools that used peer leaders to promote studying saw academic gains equivalent to moving from average to top-third performance. Even public health campaigns that correct misperceptions-like telling teens most people don’t drink heavily-work better than scare tactics. Social influence is a tool. Like any tool, it depends on how it’s used.

Why do I feel pressured to do things I don’t want to?

It’s not you-it’s your brain. When you’re uncertain, your brain automatically scans your social environment for clues. This is called social proof, and it’s an evolutionary survival mechanism. If your tribe did something, you did too. Today, it’s not about lions and berries-it’s about which sneakers to buy or whether to join a social trend. The feeling of pressure comes from your brain trying to avoid social exclusion. It’s not weakness. It’s biology.

Are some people more easily influenced than others?

Yes. Research shows susceptibility varies from 0.15 to 0.85 across individuals. Adolescents are more vulnerable because their brains are still developing self-regulation. People in dense social networks, collectivist cultures, or those with low self-esteem are also more likely to conform. But it’s not fixed. Your environment shapes your susceptibility. Change your circle, and you change how easily you’re influenced.

How can I protect myself from unwanted social influence?

Start by noticing it. Ask yourself: ‘Am I doing this because I believe it, or because everyone else is?’ Keep a journal of moments when you feel pressured to conform. Then, create distance-pause before acting. Seek out diverse opinions. Surround yourself with people who encourage independent thinking. And remember: belonging doesn’t require blind conformity. True connection comes from being yourself, not from pretending to be like others.

Hariom Sharma

February 21, 2026 AT 09:10Bro, this hits different in India. We don't even need studies to prove this - just look at wedding seasons. Everyone buys the same gold jewelry, wears the same designer sherwanis, even if they can't afford it. Why? Because not doing it = social death. My cousin skipped the big party last year and got ghosted by his entire extended family. It's not peer pressure. It's survival.

And yeah, the 'Friends for Life' thing? We've been doing this for decades with dandiya circles. If the cool kids start dancing differently, the whole group follows. No lectures. Just vibes.

Also, social media here? 90% of teens think everyone's binge-drinking during college fest season. Reality? Like 12%. But the *perception* is what drives the behavior. Mind blown.

Nina Catherine

February 22, 2026 AT 09:52omg yes!! i was just thinkin abt this yesterday when my roomie started drinking oat milk because her roommate did and now SHE thinks it’s ‘better’ even tho she’s lactose tolerant lmao

and like… i’ve noticed in my office, people start using the same slang. ‘That’s so sus’ ‘no cap’ ‘vibes’ - it’s not even conscious. we just mirror. i think it’s why i started saying ‘like’ like 5x in a sentence. i swear i didn’t even notice until my mom called me out.

also the part about status gap? 100%. i’d never copy my boss’s habits… but i’ll totally copy the person who’s chill but respected. like that one intern who always brings snacks and doesn’t talk much? everyone started bringing snacks. no one said anything. it just happened.

Taylor Mead

February 23, 2026 AT 21:00Real talk - this whole thing is just evolution on autopilot. Our brains are still running on hunter-gatherer firmware. Back then, if you didn’t eat what the group ate, you got kicked out. Now? You don’t buy the same sneakers and you get mocked on TikTok.

What’s wild is how little we realize we’re doing it. I used to think I made my own choices. Turns out I bought my first electric toothbrush because my gym buddy had one. Not because I needed it. Because he looked like he knew something I didn’t.

And yeah, the ‘status gap’ thing? Spot on. I’ve seen managers try to force change. Doesn’t work. But let one respected mid-level guy start doing something? Suddenly the whole team’s on board. No one wants to be the outlier. Not even the loud ones.

Amrit N

February 25, 2026 AT 09:37yo this is so true i was just thinkin bout how my cousin started doin yoga after her friend did it and now she’s all ‘i found my peace’ lol

but like… i dunno if it’s even about belonging. sometimes it’s just… laziness? like why think for yourself when you can just copy someone who seems to have it figured out?

also social media makes it worse. i saw 3 people post ‘i quit caffeine’ and now i’m like… maybe i should too? even tho i love coffee. just bc it looked like everyone was doin it.

also typo sorry lol

Courtney Hain

February 26, 2026 AT 02:51Let me tell you something - this whole ‘social influence’ narrative is a psyop. The real reason people conform isn’t biology or belonging. It’s because the elite *engineered* it. DeepMind’s model? Sold to advertisers. ‘Influence-as-a-service’? That’s not research - that’s weaponized social engineering.

Think about it. Every trend you think you chose - minimalism, plant-based diets, ‘self-care’ - was pushed by algorithms that tracked your social graph and targeted your susceptibility score. They don’t sell products. They sell identity templates. And they know exactly which people will buy them - the ones with low self-esteem, collectivist backgrounds, or dense networks.

The CDC’s ‘Friends for Life’ program? Cute. But who funded it? Big Pharma? Tobacco? No - it was the same folks who run TikTok’s ad platform. They don’t want you to quit vaping. They want you to quit vaping *and then buy their nicotine patches*.

Pluralistic ignorance? That’s just the cover. The real game is predictive manipulation. They don’t need to convince you. They just need to know you’ll follow the herd. And they’ve been building this system since the 90s. You’re not being influenced. You’re being *calculated*.

Robert Shiu

February 27, 2026 AT 02:12Man, I’ve seen this play out in my classroom. A kid started showing up early to study. No one said anything. But within two weeks? Half the class was there. Not because we told them to. Because they saw someone doing it - and it just felt… right.

And it’s not just students. My team at work? We were terrible at recycling. Then one guy started bringing his own mug and composting lunch. Didn’t say a word. Just did it. Now we have a full compost bin. No policy. No posters. Just one quiet person modeling it.

It’s not about pressure. It’s about visibility. You don’t need to convince someone. You just need to show them it’s possible. And then… they’ll do it without realizing why.

Also - if you’re trying to change something? Stop preaching. Start modeling. It’s way more powerful.

Greg Scott

February 27, 2026 AT 07:16Yeah. I used to think I was immune. Then I realized I bought the same laptop as my roommate because he said it was ‘reliable.’ I didn’t research it. Didn’t compare specs. Just copied him.

Turns out I’m not special. We’re all just herd animals with smartphones.

Scott Dunne

February 27, 2026 AT 10:24While I acknowledge the empirical studies cited, I must express my profound skepticism regarding the moral underpinnings of this narrative. To suggest that conformity is an evolutionary adaptation rather than a failure of personal discipline is not merely inaccurate - it is dangerously permissive. In Ireland, we value individual integrity above social conformity. To normalize mimicry as biological inevitability is to surrender to the tyranny of the majority. This is not science. It is surrender dressed in academic language.

Furthermore, the notion that ‘influence’ can be ethically deployed is naive. Any system that measures susceptibility for commercial gain is inherently corrupt. The state must intervene. Not to suppress influence - but to outlaw its monetization. We do not allow the manipulation of children’s psychology for profit. Why, then, do we permit it for adults?

This is not a psychological phenomenon. It is a civilizational decline.