How Climate Change May Influence the Spread of Skin‑Dwelling Parasites

Oct, 5 2025

Oct, 5 2025

Skin Parasite Risk Calculator

Climate Conditions

Enter the average temperature and humidity levels in your region to estimate the risk of skin parasites.

Risk Assessment Result

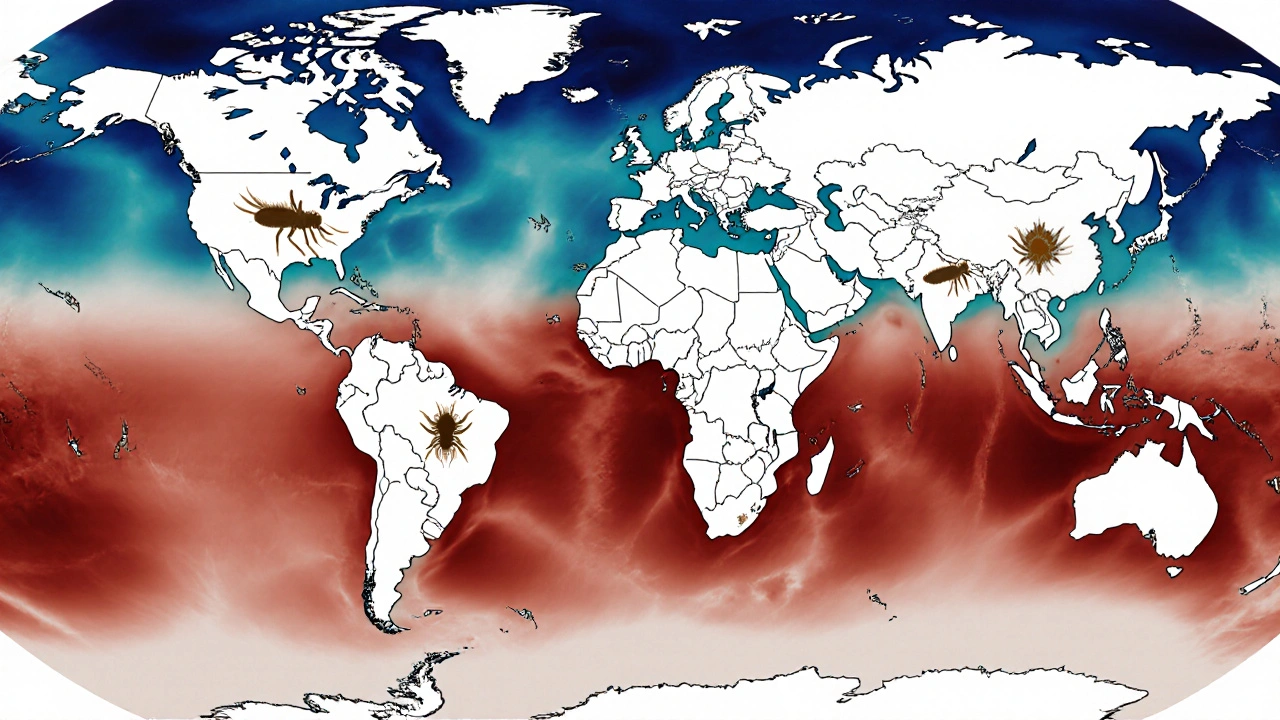

Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events are reshaping ecosystems worldwide. One hidden impact is how these changes help skin‑dwelling parasites move into new territories, putting fresh eyes on old itching problems. This article unpacks which parasites are most at risk, why climate matters, and what communities can do to stay ahead.

Key Takeaways

- Warmer, more humid climates speed up the life cycles of many skin parasites, extending their season and geographic reach.

- Species such as the scabies mite, sand flea, chigger, and hookworm larvae have already shown northward expansions in the past decade.

- Public health risks rise when vulnerable populations-children, the elderly, and outdoor workers-encounter novel infestations.

- Surveillance, community education, and climate‑adapted control measures are essential to limit outbreaks.

- Clinicians should update diagnostic checklists to include emerging parasites in regions previously considered low‑risk.

What are skin‑dwelling parasites?

Skin‑dwelling parasites are tiny organisms that live on or just beneath the human epidermis, feeding on skin cells, blood, or tissue fluids. Common examples include:

- Scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei) - a microscopic arachnid that burrows into the skin, causing intense itching.

- Sand flea (Tunga penetrans) - a burrowing flea that embeds its abdomen into the skin of the foot.

- Chigger (family Trombiculidae) - larval mites that latch onto skin, inject digestive enzymes, and cause red welts.

- Hookworm larvae (Ancylostoma braziliense) - when they penetrate bare skin, they cause cutaneous larva migrans.

Collectively, these organisms fall under the broader category of skin‑dwelling parasites, which are a type of ectoparasite that directly interact with human skin.

How climate variables drive parasite life cycles

Climate change alters two key environmental factors that dictate parasite success: temperature and humidity. Both affect development speed, survival outside a host, and the ability to locate new hosts.

- Temperature boost: Most skin parasites have optimal development temperatures between 20‑30°C. A 2°C rise can cut the egg‑to‑adult cycle of the scabies mite from 10days to around 7days, allowing more generations per season.

- Humidity lift: High relative humidity (≥80%) prevents desiccation of free‑living stages, especially the larvae of sand fleas and hookworms. Warmer, wetter air lets them survive longer on soil or beach sand.

- Extended season: Mild winters reduce seasonal die‑offs. In parts of northern Europe, winter temperatures now stay above the 10°C threshold needed for chigger activity, meaning they can appear from early spring through late autumn.

Evidence of climate‑driven range expansions

Several recent studies map the northward movement of skin parasites. The table below summarizes key species, their historical climatic limits, and projected changes by 2050 under a moderate emissions scenario (RCP4.5).

| Parasite | Current optimal temperature (°C) | Current optimal humidity (%) | Typical latitude range | Projected 2050 latitude shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scabies mite | 22‑28 | 70‑90 | 30°N-45°N | ≈5°northward |

| Sand flea | 24‑30 | 80‑95 | 15°S-20°N | Up to 10°northward into subtropical zones |

| Chigger | 18‑26 | 75‑85 | 35°N-55°N | ≈7°northward, reaching parts of Scandinavia |

| Hookworm larvae | 25‑31 | 85‑95 | 10°S-30°N | 5°‑7°northward, affecting coastal regions of the UK and Ireland |

These shifts are not theoretical. A 2023 UK‑based surveillance program recorded the first chigger‑related dermatitis cases in southern Scotland, a region previously too cool for the parasite.

Public health implications

When parasites move into new areas, the local health system often lacks experience diagnosing and treating them. Consequences include:

- Increased morbidity: Untreated scabies can lead to secondary bacterial infections and, in dense living conditions, outbreaks.

- Economic burden: Out‑of‑pocket costs for creams, ivermectin courses, and lost workdays rise sharply during outbreak spikes.

- Vulnerable groups at higher risk: Children playing barefoot on warm beaches are prime targets for hookworm larvae; elderly residents in poorly insulated homes may suffer more severe sand‑flea infestations.

Moreover, climate‑driven migration of parasites can intersect with other stressors-e.g., flood‑related displacement-creating compound health crises.

Monitoring, prevention, and control strategies

Effective response starts with early detection and community‑level action. Below are practical measures for health authorities and individuals.

- Enhanced surveillance: Deploy rapid‑response teams to track skin infestation reports. Mobile apps that let citizens upload photos of lesions can feed real‑time data to public health dashboards.

- Environmental management: Maintain dry, well‑ventilated indoor spaces to limit mite survival. In coastal areas, regular sand raking and use of larvicidal agents reduce hookworm larvae density.

- Education campaigns: Teach parents about the importance of footwear on beaches and the risks of walking barefoot in warm, humid soils.

- Access to treatment: Ensure primary‑care clinics stock topical permethrin, oral ivermectin, and appropriate antibiotics for secondary infections.

- Climate‑adapted guidelines: Update national skin‑health advisories each decade to reflect shifting risk zones based on temperature and humidity models.

Clinical checklist for emerging skin parasites

When a patient presents with unexplained itching or rash, consider the following questions:

- Has the patient traveled to or lived in a region that experienced recent warming trends?

- Is there recent exposure to sandy beaches, riverbanks, or forest floor during warm, humid days?

- Do lesions appear in typical locations for specific parasites (e.g., between toes for sand flea, wrists/ankles for chiggers)?

- Are there signs of secondary bacterial infection (pus, crusting) that may require antibiotics?

- Is the patient in a high‑risk group (young children, elderly, immunocompromised)?

Answering these points helps narrow the likely culprit and speeds up appropriate therapy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will warmer summers increase scabies cases in Europe?

Yes. Warmer summers shorten the mite’s life cycle, allowing more generations per season. Recent data from Germany and the UK show a 12‑15% rise in reported cases during the past five years, correlating with above‑average summer temperatures.

Are sand fleas limited to tropical beaches?

Historically they thrive in hot, humid coastal zones, but climate projections indicate they could establish permanent populations along subtropical coastlines of southern England and northern Spain by 2040.

How can I protect my children from chigger bites?

Dress them in long sleeves and trousers when playing in tall grass, apply insect repellent containing DEET or picaridin, and shower promptly after outdoor activities to wash away any unattached larvae.

Is ivermectin effective against hookworm skin larvae?

A single dose of oral ivermectin (200µg/kg) is highly effective for cutaneous larva migrans caused by hookworm larvae, often clearing lesions within 48hours.

What role does humidity play in parasite survival?

High humidity prevents desiccation of free‑living stages such as eggs, larvae, or pupae. In dry conditions, many parasites cannot survive more than a few hours, whereas at ≥80% relative humidity they can persist for days to weeks.

Anna Marie

October 5, 2025 AT 13:01Considering the mechanisms mentioned, the acceleration of parasite life cycles due to rising temperature and humidity underscores the need for proactive public‑health planning. Integrating climate data into existing surveillance platforms can help anticipate outbreaks before they become widespread. Health agencies should prioritize training for frontline workers on the identification of emerging skin‑dwelling parasites, especially in regions experiencing rapid climatic shifts.

Abdulraheem yahya

October 8, 2025 AT 13:16The interplay between ambient temperature increases and parasite reproductive rates creates a cascading effect that extends the viable season for organisms like the scabies mite, sand flea, and chigger. When the average daily temperature rises even by a modest two degrees Celsius, the developmental period shortens, resulting in more generational turnover within a single summer. This dynamic is further amplified by heightened relative humidity, which protects eggs and larvae from desiccation, allowing them to persist longer on soil and sand surfaces. In coastal communities, where humidity frequently exceeds eighty percent, sand flea populations can establish stable colonies that were previously limited to tropical locales. Moreover, the northward migration of these species is not merely a theoretical projection; recent case reports from southern Scotland and northern England illustrate that the organisms are already colonizing new habitats. The epidemiological implications are profound, as local clinicians may lack experience diagnosing conditions such as cutaneous larva migrans or chigger‑induced dermatitis, leading to delayed treatment and increased morbidity. Public‑health infrastructure must therefore adapt by incorporating climate‑adjusted risk maps into their routine monitoring. Community education campaigns should emphasize practical protective measures, such as wearing appropriate footwear on beaches and maintaining indoor environments that discourage mite proliferation. Access to effective therapeutics, including permethrin and ivermectin, must be ensured, particularly in underserved areas where outbreaks could strain limited resources. Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration between climatologists, entomologists, and medical professionals will be essential to develop predictive models that can guide timely interventions.

Preeti Sharma

October 11, 2025 AT 13:31One might argue that the narrative of climate‑driven parasite expansion overshadows the deeper philosophical question of humanity's relationship with the microscopic world. While the data points to a clear correlation, it also invites contemplation on the delicate balance we maintain with unseen organisms that have co‑evolved with us for millennia. The rising tide of temperature is not merely a backdrop; it is an active participant in reshaping ecological hierarchies, urging us to reconsider the ethical dimensions of our interventions. If we accept the premise that our actions alter the habitats of these minute beings, we must also accept the responsibility to mitigate the unintended consequences that follow. Thus, the discussion should move beyond statistics to a more nuanced discourse that acknowledges both the scientific and existential layers of this phenomenon.

Ted G

October 14, 2025 AT 13:46While mainstream reports focus on temperature graphs and humidity charts, there is a quieter agenda at play, one that ties global health surveillance to broader geopolitical strategies. The deployment of advanced monitoring tools in remote regions often coincides with increased military presence and data collection initiatives that extend beyond public health. This overlap suggests a layered motive, where the tracking of skin‑dwelling parasites serves as a convenient front for more expansive intelligence operations, subtly embedding surveillance infrastructure under the guise of disease control. Such convergence of interests warrants a cautious appraisal of the narratives presented by official channels.

Miriam Bresticker

October 17, 2025 AT 14:01Life is stiill a thread of interwoven fates, 🌍 and the warming earth pulls at those threads in the most unseen ways. When temp rises, even the tiniest critters feel the shift, 🌡️ looking for new places to call home. It's like a silent dance where each step changes the rhythm of our skin's own ecosystem. So, we must stay aware, actwisely, and maybe add a dash of wonder to the science 🧬✨.

Claire Willett

October 20, 2025 AT 14:16Deploy integrated vector surveillance systems leveraging GIS analytics to enhance early detection of ectoparasite emergence.

olivia guerrero

October 23, 2025 AT 14:31Wow!!! This is absolutely fascinating!!! The way climate change can literally change where little bugs live is just mind‑blowing!!! Imagine the possibilities for preventive health strategies!!! 🌿🌡️💪

Dominique Jacobs

October 26, 2025 AT 13:46Listen up-this is a call to action! The data is clear and the stakes are high, so we need to mobilize our communities now! Educate families, distribute treatments, and push for climate‑responsive health policies! No excuses, no delays-let's turn knowledge into power and protect those most vulnerable!

Claire Kondash

October 29, 2025 AT 14:01In the grand tapestry of existence, the microscopic wanderers we call skin parasites are but humble threads, yet their movements echo the larger symphony of planetary change. 🌐 When the climate warms, these threads stretch, seeking new fabrics upon which to weave their life cycles, and in doing so, they remind us that even the smallest actors are participants in the drama of earth's evolution. 🧵🌀 As temperatures climb and humidity rises, the developmental clocks of scabies mites, sand fleas, and chiggers accelerate, compressing generational timelines and expanding geographic footprints-a process that mirrors how humanity reshapes landscapes at a macro scale. This parallel invites us to reflect on the interconnectedness of all scales of life, urging a humility that recognizes our role not as masters but as co‑inhabitants of a shared biosphere. 🌱 Therefore, the rising incidence of cutaneous infestations becomes a subtle but potent indicator, a biological barometer signaling the health of our environment, and it challenges public‑health frameworks to adopt a more holistic, climate‑integrated perspective. 🌡️💡 In embracing this view, we not only improve diagnostic vigilance but also foster a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance that sustains both human comfort and ecological integrity. 🌏💚

Matt Tait

November 1, 2025 AT 14:16Another predictable hype cycle.