Esophageal Cancer Risk: Chronic GERD and the Red Flags You Can't Ignore

Dec, 19 2025

Dec, 19 2025

If you’ve had heartburn for years-maybe even decades-you might think it’s just part of life. But chronic GERD isn’t just uncomfortable. It’s a silent alarm that could signal a much bigger threat: esophageal cancer. The truth is, most people with GERD never develop cancer. But for some, the constant burn of stomach acid slowly rewires the lining of the esophagus, setting off a chain reaction that can end in malignancy. And the scary part? By the time symptoms become obvious, it’s often too late.

How GERD Turns Into Cancer

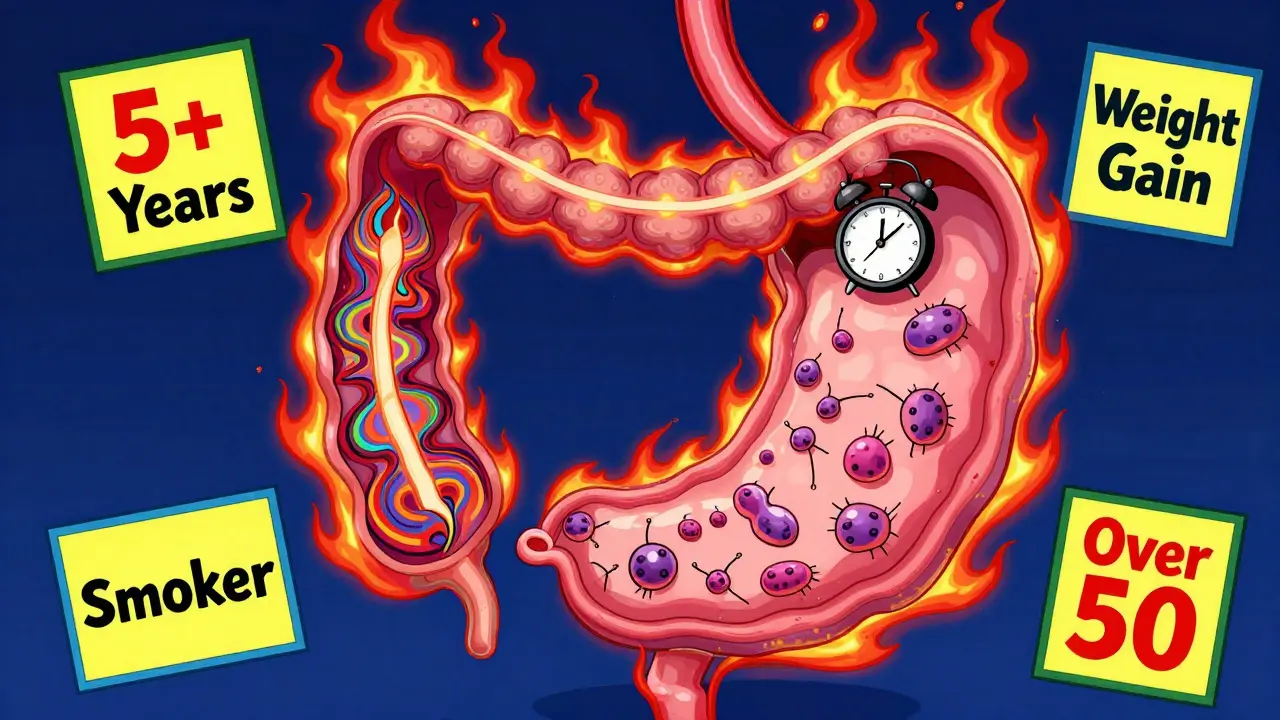

Your esophagus is built to move food down to your stomach. It’s not built to handle stomach acid. When you have chronic GERD, that acid keeps coming back up, day after day, year after year. Over time, your body tries to protect itself by changing the cells in the esophagus. Instead of the normal flat, pink tissue, they start looking more like the cells in your stomach. This is called Barrett’s esophagus. Barrett’s esophagus isn’t cancer. But it’s the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma-the most common type of esophageal cancer in the U.S. Studies show that people with GERD for five or more years are five times more likely to develop Barrett’s than those without it. And while only 0.5% to 2% of GERD patients develop Barrett’s, and only 0.2% to 0.5% of those progress to cancer each year, the sheer number of people with GERD makes this a massive public health issue. About 20% of Americans have GERD. That means hundreds of thousands are walking around with a hidden risk. The key isn’t fear. It’s awareness. If you’ve had daily or weekly reflux for five years or more, especially if you’re a man over 50, white, overweight, or a smoker, you’re in a higher-risk group. The progression isn’t random. It’s predictable. And that means it’s preventable-if you catch it early.The Real Red Flags: When to Act Now

Most people with early-stage esophageal cancer feel fine. That’s why it’s so deadly. By the time they notice something’s wrong, the cancer has often spread. But there are clear warning signs that shouldn’t be ignored. These aren’t vague symptoms. They’re measurable, specific, and backed by data.- Dysphagia-feeling like food gets stuck in your chest or throat-is the most common symptom, present in 80% of cases at diagnosis. It usually starts with solids, then moves to liquids. If you’re avoiding steak, bread, or even apples because they feel like they’re catching, don’t brush it off.

- Unexplained weight loss of more than 10 pounds in six months, without trying, is a major red flag. It happens in 60-70% of diagnosed cases. Your body is fighting something, and it’s not just your diet.

- Heartburn that’s gotten worse or changed after age 50, especially if it’s happening more than twice a week for five years straight, is a signal. Nearly 90% of people with esophageal adenocarcinoma had chronic GERD before diagnosis.

- Food impaction-where food actually gets stuck and you have to drink or cough to clear it-happens in 30-40% of cases. This isn’t occasional choking. It’s recurring.

- Chronic hoarseness or cough lasting more than two weeks, especially if you don’t smoke or have allergies, could mean acid is irritating your vocal cords. It’s not just a cold. It’s a warning.

Who’s Most at Risk? The Numbers Don’t Lie

Not everyone with GERD is at equal risk. The data shows clear patterns. The American Cancer Society and Mayo Clinic agree: the highest-risk group is white men over 50 with chronic GERD and at least two other risk factors.- Gender: Men are 3 to 4 times more likely than women to develop esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Age: 90% of cases occur in people over 55. Risk climbs after 50.

- Race: White non-Hispanic Americans have three times the rate of adenocarcinoma compared to Black Americans.

- Weight: Obesity (BMI ≥30) doubles or triples your risk. Fat around the abdomen increases pressure, forcing acid upward. Studies show losing 5-10% of your body weight cuts GERD symptoms by 40%.

- Smoking: Current or former smokers have 2-3 times higher risk. Even quitting reduces cancer risk by half within 10 years.

- Family history: If a close relative had esophageal cancer, your risk goes up. It’s not genetic luck-it’s shared environment, diet, and lifestyle.

What You Can Do: Prevention That Actually Works

You can’t change your age or gender. But you can change what you do every day. And those changes matter.- Take your PPIs as prescribed. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole or esomeprazole don’t just relieve heartburn. They lower your cancer risk by 70% if taken consistently for five years or more. Don’t stop them just because you feel better. The damage heals slowly.

- Quit smoking. It’s the single most effective lifestyle change you can make. Within a decade, your risk drops by half.

- Limit alcohol. Heavy drinking (3+ drinks/day) raises the risk of squamous cell carcinoma, a different type of esophageal cancer. Stick to one drink a day for women, two for men.

- Manage your weight. Losing even 10 pounds can make a huge difference. Less belly fat = less pressure on your stomach = less acid reflux.

- Get screened. If you’re a white male over 50 with chronic GERD and two other risk factors, an upper endoscopy is recommended. It’s a quick, outpatient procedure. A camera goes down your throat. They look for Barrett’s. If they find it, they take tiny tissue samples. It’s not fun-but it saves lives.

The Future: Better Screening, Better Outcomes

The good news? Screening is getting smarter. The American Gastroenterological Association now uses a tool called "BE MAPPED"-a risk calculator that uses seven factors (age, sex, BMI, smoking, GERD duration, family history, race) to predict your chance of having Barrett’s. It’s 85% accurate. New methods are emerging too. The Cytosponge is a pill you swallow that unfurls into a tiny sponge on a string. It’s pulled out, collecting cells from your esophagus. No sedation. No scope. A 2022 Lancet study showed it catches 79.9% of Barrett’s cases. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s coming. Researchers are also looking at genetics. Some people have gene variants-like in the CRTC1 gene-that make them more likely to develop Barrett’s after years of GERD. In the future, a simple blood or saliva test might tell you if you’re in the high-risk group, even before symptoms get bad.What Happens If You’re Diagnosed Early?

The survival rate for esophageal cancer is only 21% overall. That number is horrifying. But here’s the hope: if caught early-when it’s still in the esophagus and hasn’t spread-the 5-year survival rate jumps to 50-60%. That’s not a guarantee. But it’s a chance. And that chance only exists if you act before symptoms become severe. Endoscopic surveillance for Barrett’s patients with early cell changes (dysplasia) reduces cancer deaths by 60-70%. That’s not a small number. That’s life-saving. The truth is, esophageal cancer isn’t something that just happens. It’s the end result of a long, slow process. And that process can be interrupted. With medication. With lifestyle changes. With screening. With action. Don’t wait for the cough to turn into a scream. Don’t wait for food to get stuck every time you eat. Don’t wait for weight loss to become obvious. If you’ve had GERD for five years or more-and you’re in a high-risk group-talk to your doctor. Ask for an endoscopy. It’s not a big deal. It’s the most important thing you can do for your future self.Is GERD the same as occasional heartburn?

No. Occasional heartburn-once or twice a month-is common and usually harmless. GERD is chronic acid reflux happening at least twice a week for several months or longer. It’s when your body starts changing to cope with the acid, which can lead to Barrett’s esophagus and eventually cancer.

Can I just take antacids instead of PPIs?

Antacids like Tums or Rolaids give quick relief but don’t stop acid production. They won’t prevent Barrett’s esophagus or reduce cancer risk. PPIs are the only medications proven to lower cancer risk by reducing acid over the long term. If you have chronic GERD, PPIs are the standard of care.

Do I need an endoscopy if I have GERD but no symptoms?

Symptoms aren’t always a good guide. Many people with Barrett’s esophagus have little to no heartburn. If you’re a white male over 50 with chronic GERD (5+ years) and other risk factors like obesity or smoking, you should be screened-even if you feel fine. The goal is to catch changes before they become cancer.

Can losing weight reverse Barrett’s esophagus?

Losing weight won’t reverse Barrett’s, but it can stop it from getting worse. Studies show weight loss reduces acid reflux, which slows or halts further cell changes. In some cases, with long-term acid suppression and weight loss, Barrett’s can regress-but only if caught early.

Is esophageal cancer hereditary?

It’s not directly inherited like some cancers, but having a close family member with esophageal cancer does raise your risk. This is likely due to shared lifestyle factors-diet, smoking, obesity-rather than genes. Still, if you have a family history, talk to your doctor about earlier screening.

Jerry Peterson

December 21, 2025 AT 02:43I’ve had GERD for 12 years. Took PPIs like clockwork, lost 35 pounds, quit smoking. Got my endoscopy last year - no Barrett’s. Just goes to show, you don’t have to live with it. Your body listens when you treat it right.

Adrian Thompson

December 22, 2025 AT 00:50So let me get this straight - the government wants you to take PPIs for life because Big Pharma says so? Meanwhile, the real cause is glyphosate in your bread and fluoride in the water. They don’t want you to know that acid reflux is your body’s way of detoxing from chemtrails. Endoscopy? Nah. Just drink apple cider vinegar and pray.

Jackie Be

December 23, 2025 AT 18:07OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE HAD HEARTBURN SINCE 2018 AND I THOUGHT IT WAS JUST SPICY TACOS 😭 I’M 52 AND WHITE AND MY BELLY IS A BALLOON I NEED TO GO NOW I’M SCARED BUT ALSO KINDA READY TO BE A HEALTH HERO 💪

Jason Silva

December 24, 2025 AT 16:46Bro this is wild 🤯 I was just telling my cousin last week he needs to stop eating pizza before bed. He’s 58, smokes, weighs 240 - total ticking time bomb. I sent him this post. He said ‘nah I’m fine’ 😂 I’m just waiting for him to come back screaming for help. Save yourself, people. Your esophagus ain’t a volcano.

mukesh matav

December 25, 2025 AT 08:17In India, we don’t have much of this problem. People eat spicy food all day, drink buttermilk, sleep on left side. No PPIs needed. Maybe it’s not the acid - maybe it’s the Western diet. Just saying.

Peggy Adams

December 26, 2025 AT 23:16So basically if you’re a white guy over 50 who likes beer and doesn’t work out, you’re basically already dead? Cool. I’ll just ignore this until I can’t swallow my steak. Why bother? The system’s rigged anyway.

Theo Newbold

December 27, 2025 AT 08:49The 70% risk reduction from PPIs is based on observational studies with confounding variables. The NIH study showing lower colorectal cancer rates in GERD patients is likely due to surveillance bias - they’re getting screened for everything. No causal link proven. Endoscopy has complications. Don’t be manipulated by fear-driven medicine.

Jay lawch

December 28, 2025 AT 11:09Think about it - we’ve been conditioned to fear the body’s natural processes. Acid reflux isn’t a disease - it’s a signal. The esophagus is not failing. The system is failing. The modern diet, the sedentary life, the corporate control of healthcare - we’ve turned a physiological warning into a pharmaceutical product. The real Barrett’s isn’t in the esophagus - it’s in the collective mind that accepts pills as solutions and ignores root causes. We are the disease we treat. And the endoscopy? Just another ritual in the temple of industrial medicine.